The fixpoint and the (over)layer cake

I am a big fan of the overlay system that Nix uses to allow modular tweaks to the otherwise monolithic and centralized nixpkgs. But the rules about their two arguments are crazy. Why should packages come from self and other things from super. Is it really important ?

As I got started digging into these overlays and their mechanics, the post became a bit too involved. I decided to split it in two parts. This first part describes how overlays work, and why they have been implemented in that fashion. The next will dig deeper into the rules for a good use of

selfandsuper.

The overlay system is best described by its architect, Nicolas B. Pierron (@nbp) in his NixCon 2017 talk. For those who, like me, prefer text resources for learning, I should also mention the slides of the presentation, as well as the relevant entries in the nixpkgs manual and the nixos wiki.

Overlays primer

Nixpkgs is a large set of nix packages maintained by the community. It can be seen as a mapping between package names and their definition.

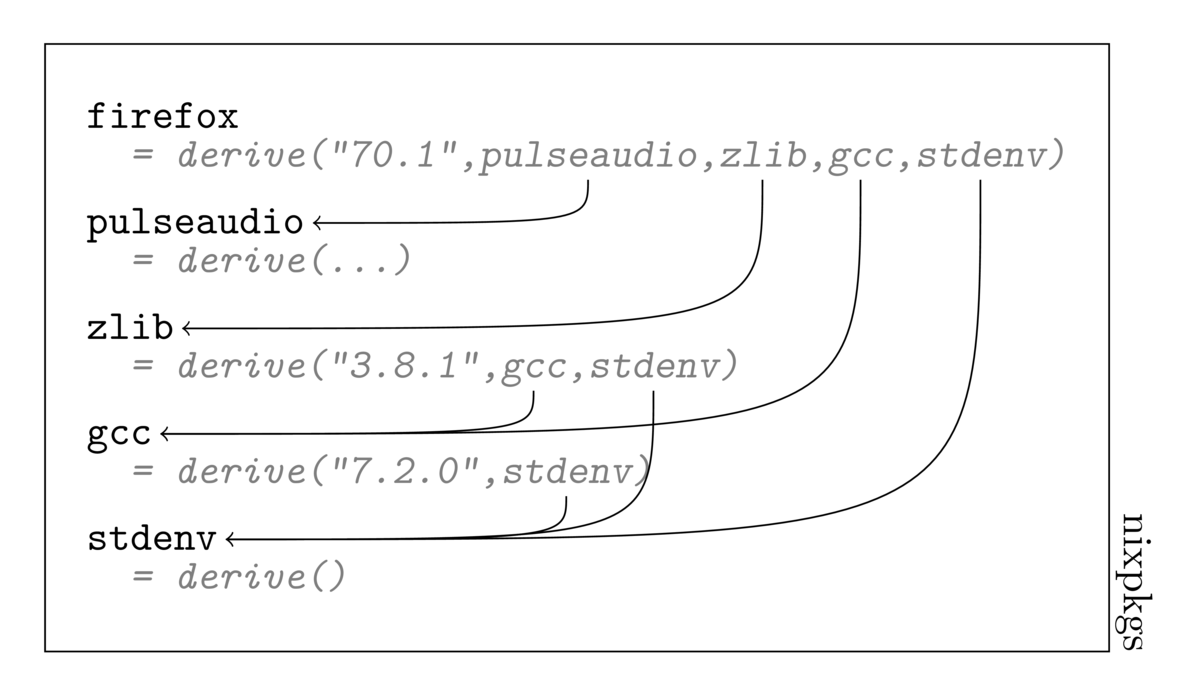

For representation purposes, we will make the assumption that a package (a derivation in nix parlance) is the result of calling a deriving (i.e. building) function with i) a version number and ii) other derivations as dependencies.

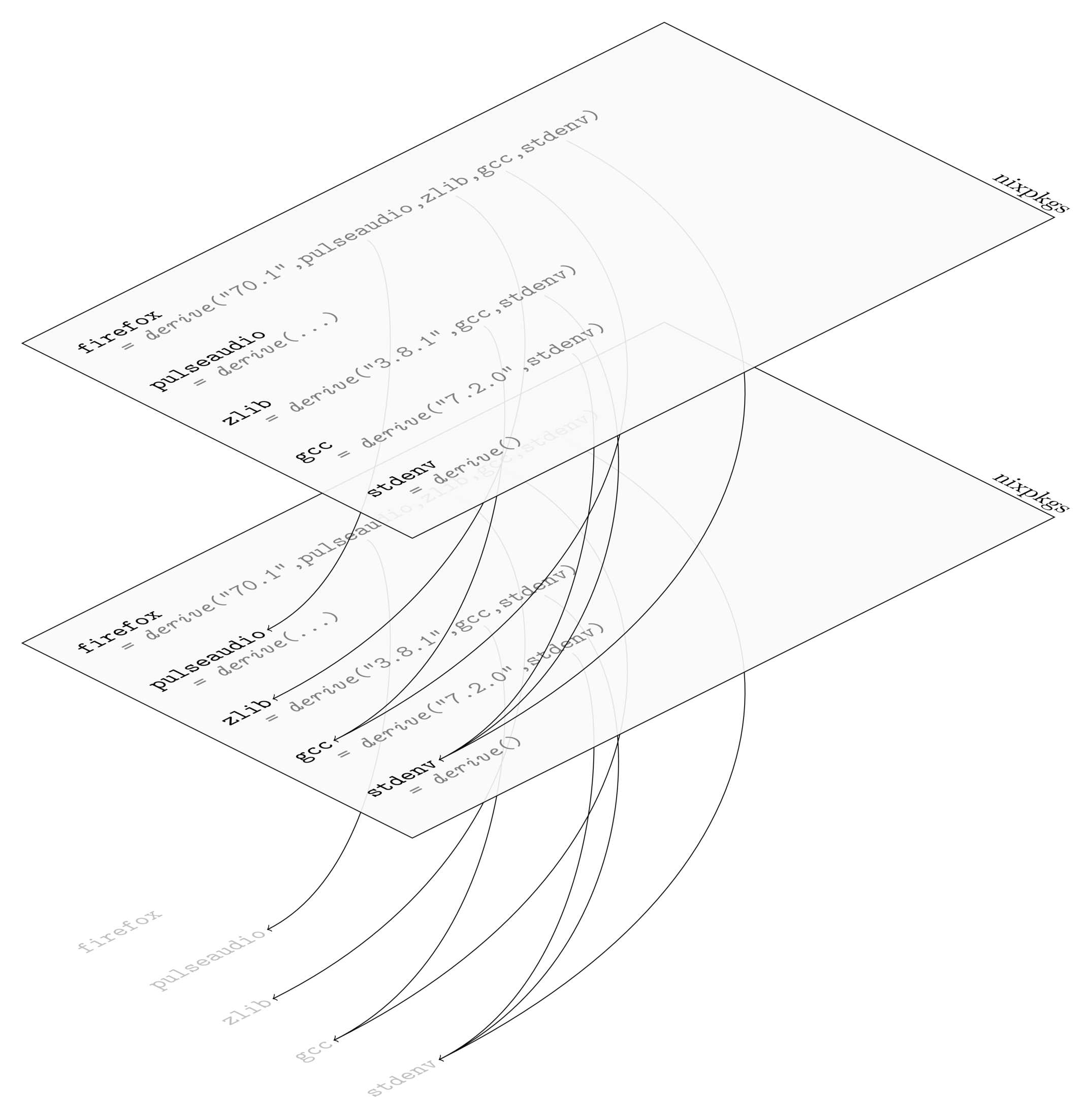

Here is a simplified view of nixpkgs as can be obtained with a trivial call like nix import <nixpkgs> {}.

We see that packages dependencies form a directed acyclic graph, a.k.a a DAG. Such graphs can be seen as simple trees for the majority of purposes. In such a graph, circular dependencies are impossible. While technically the Nix language allows to define such loops, they lead to error: infinite recursion encountered during evaluation. Properly behaved package sets do not do that, and so neither does nixpkgs.

Leaf packages are not used by any other packages. This is the case for firefox in our contrived example. A few bootstrap packages do not depend on any other packages. In our example, it is stdenv.

Nixpkgs is a huge monolith of code containing over 60k packages. In 2016, it even appeared in the 2016 edition of Github’s “State of the Octoverse” report as the #6 repo in terms of code reviewers. While busy, the repository cannot accept every custom package of nixpkgs users. Nor can it accept private, licensed or in development packages. Enter “overlays”. The feature allows to make additions and modifications to the locally available nixpkgs package set.

To add a new package or override an existing package, overlays merge the new definitions inside the main package set. This is an attribute set update operation, as defined by the corresponding nix “//” operator.

A naive overlay

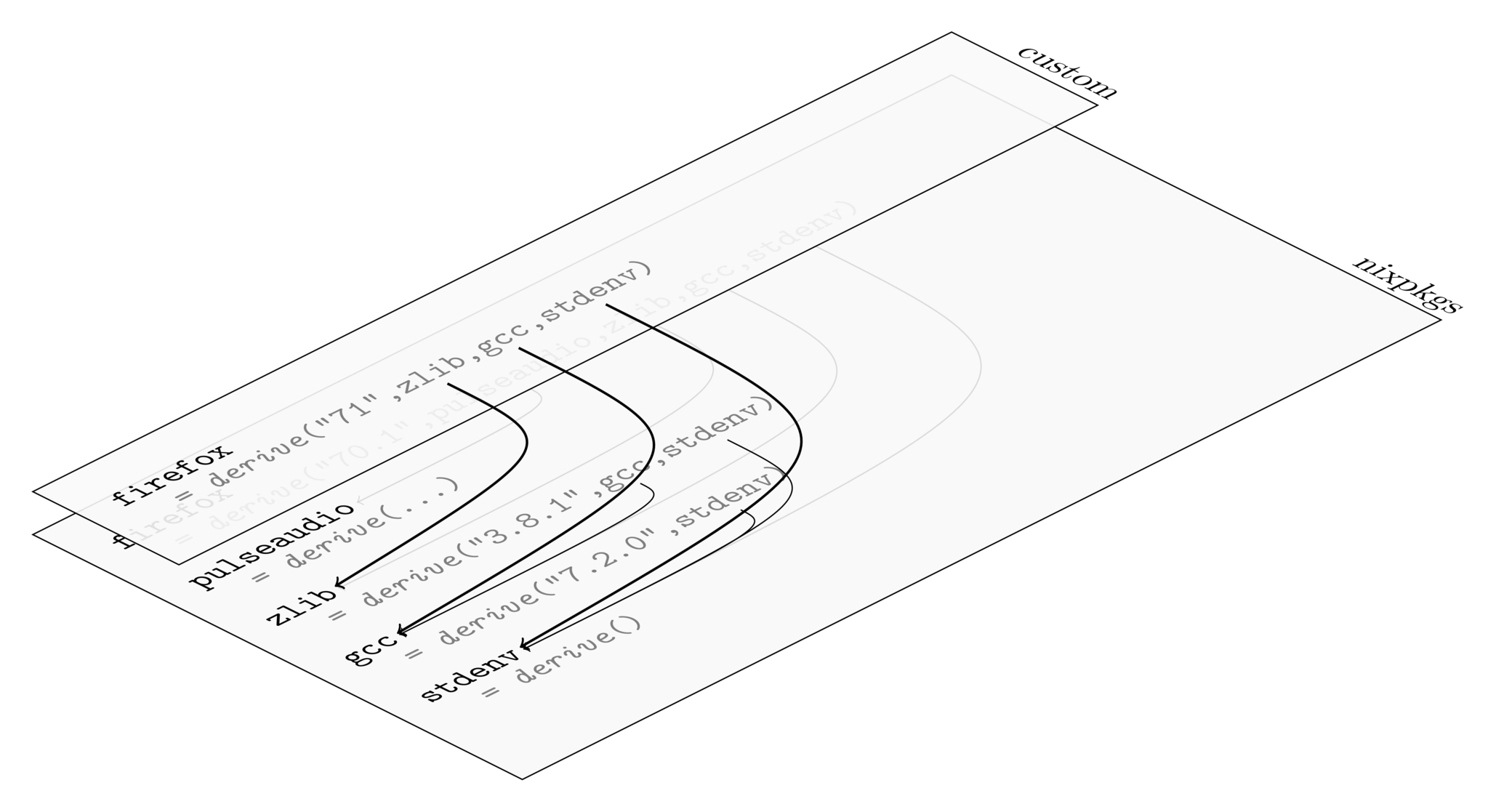

Assuming you want a firefox built without pulseaudio, and prefer to use v71 instead of v70.1 provided in nixpkgs. You would have to define a new firefox derivation, and merge it into nixpkgs like this:

let

nixpkgs = import <nixpkgs> {};

custom = {

firefox = derive("71", nixpkgs.zlib, nixpkgs.gcc, nixpkgs.stdenv)

}

in

nixpkgs // customThis gets you an updated package set where the original definition of firefox is no more visible. The attribute firefox references your new, custom version.

In the resulting package set, the attribute firefox will reference your new package. Such overlays can also be used to add new packages, by picking an attribute name that is not yet in use. For a custom version of firefox, it would also make sense to give it a unique name, like firefox-custom.

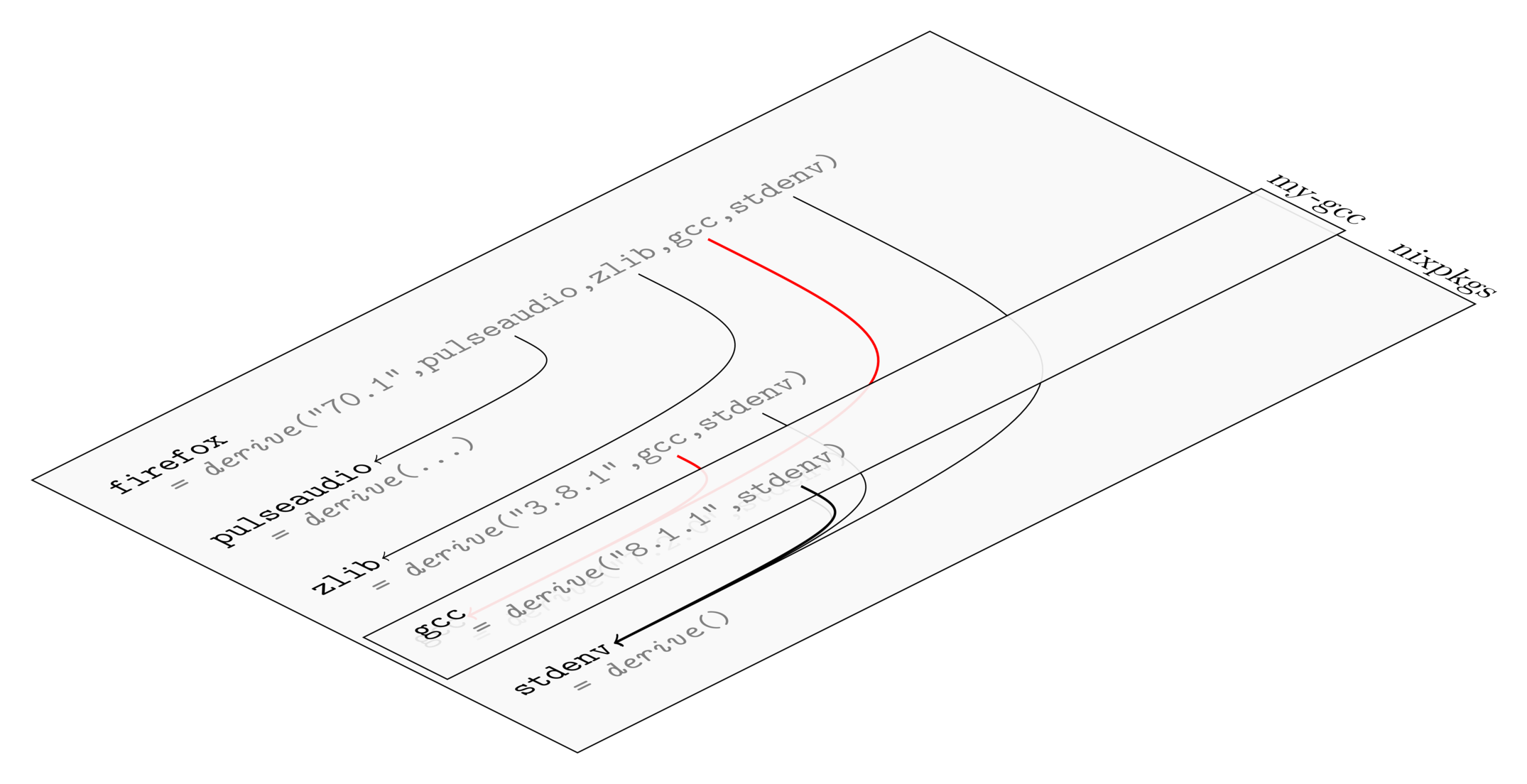

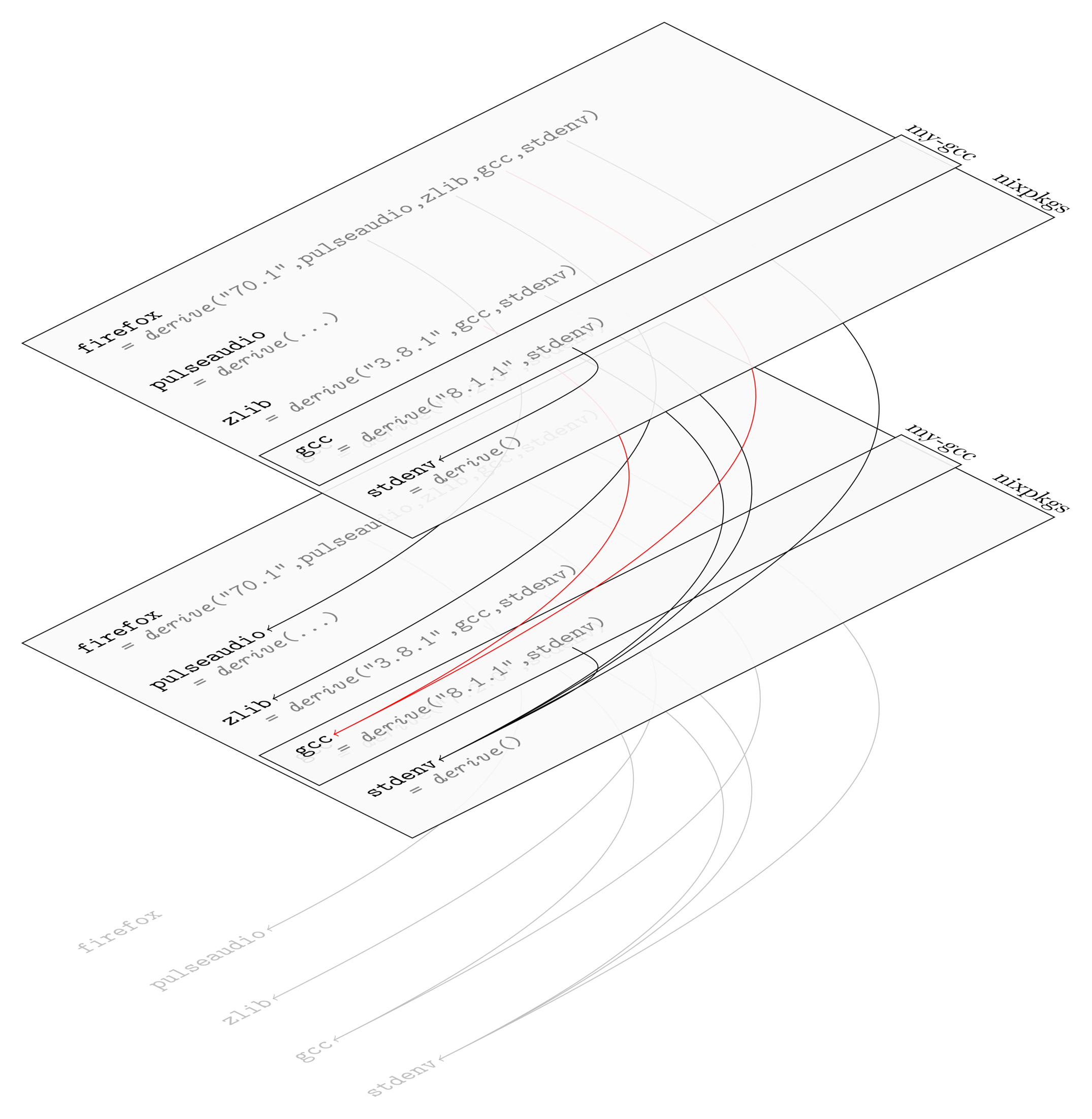

This way of overlaying packages shows its limits when you want to modify an internal package in the dependency tree. Assuming that, for some reason, you would prefer your system to be compiled with gcc v8.1.1 instead of the provided v7.2.0. Working in the same way as above, you would obtain a package set where the attribute gcc references your new package, but all of the other packages are still being compiled with the old gcc. This is highlighted by the red references edges in our representation of package sets.

Working only with attribute sets update (//), there is no way to propagate changes to an existing package set. To propagate overlays to existing packages, we need support from nixpkgs itself.

The nixpkgs fixpoint

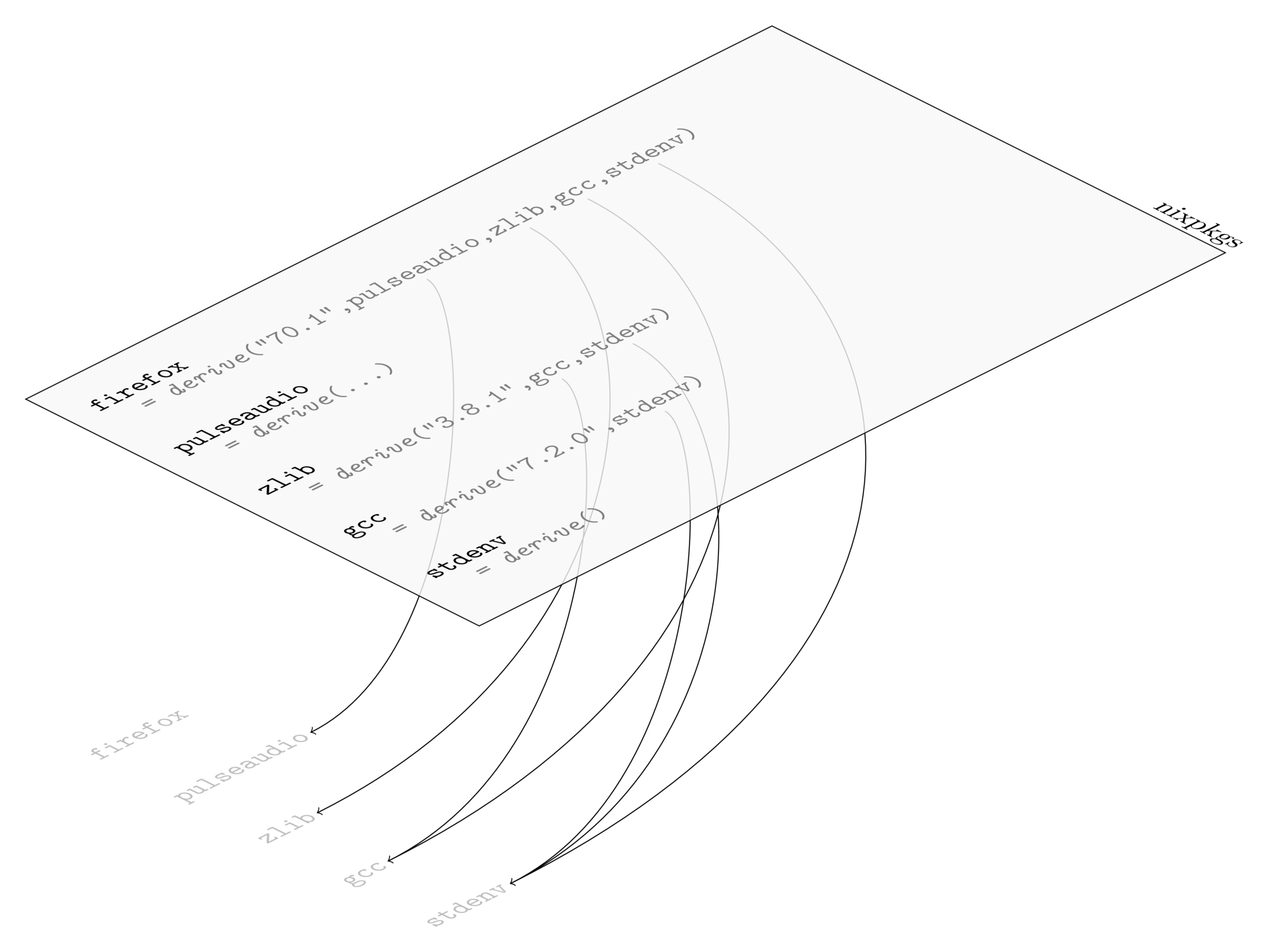

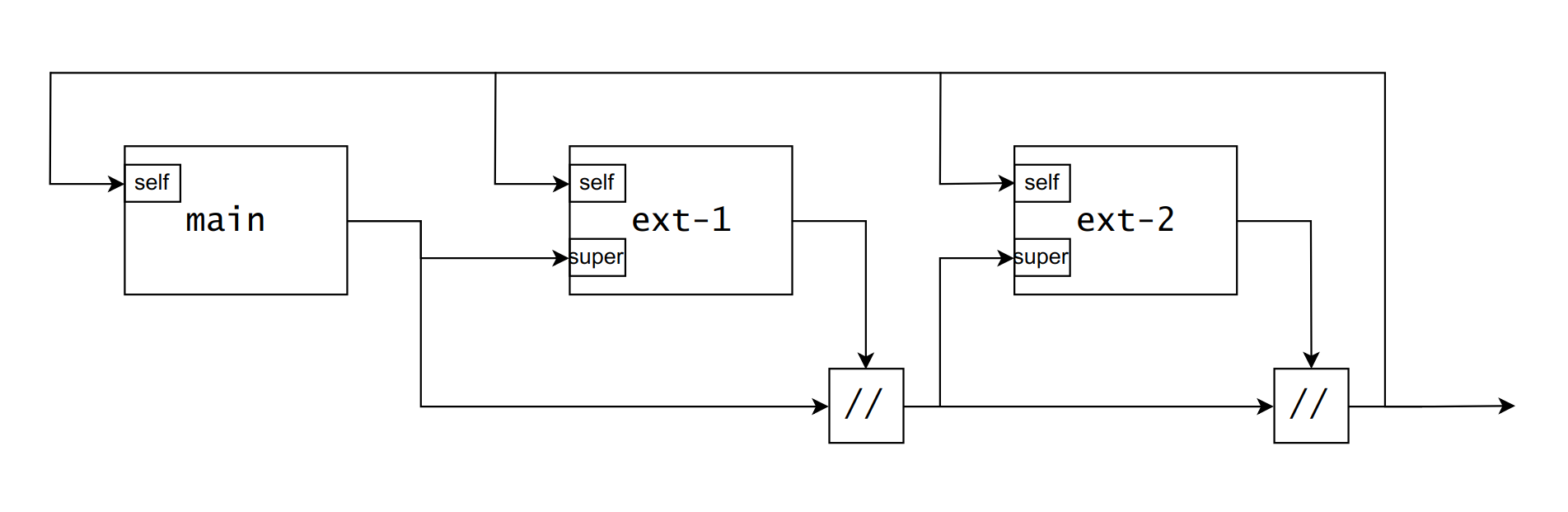

To support overlays, @nbp modified nixpkgs in such a way that it does not depend on itself directly, but on some other theoretical package set that should contain roughly the sames packages as itself. Technically, nixpkgs is designed as a function that takes as input all the dependencies used by nixpkgs. At this point, I think a picture is worth a thousand linguistic wandering.

Of course, the only package set that could possibly provide all of the required dependencies is nixpkgs itself. No problem! Let’s just pass it as the input set to nixpkgs.

You probably already heard it, but nixpkgs is implemented as a fixpoint. The term may be frightening at first glance, but the idea is just to feed the nixpkgs function to itself, forever, so that there are no more dangling dependencies in nixpkgs. In terms of code, it amounts to an infinitely recursive definition.

let

nixpkgs_fun = self: {

firefox = derive("70.1", self.pulseaudio, self.zlib, ...)

pulseaudio = ...

...

};

nixpkgs = nixpkgs_fun nixpkgs

in

nixpkgsFear not, this recursion is not infinite in practice, because the Nix language is lazy. It is even quite efficient, because the definition of nixpkgs is shared. Which means that instead of copying the same nixpkgs function over and over, the pacakge set is made to reuse itself, the same actual value, computed lazily.

Nixpkgs overlays

In nixpkgs overlays are added before feeding nixpkgs into itself. When the recursion is applied, nixpkgs uses the full stack of overlays to look for dependencies. This means that nixpkgs will catch the updated packages. I our former example with gcc, it means that all the packages depending on gcc will find the updated version, and build with it.

Actually building this package set will take some time, as none of the newly defined packages exist in the binary cache. You will be rebuilding your whole package set from scratch.

This kind of indirect references to other packages, so as to ply nicely with the nixpkgs fixpoint is done through the self argument of an overlay. That is, the first argument to the overlay function, as it is quite easy (and frequent) to mistype the arguments order. For the record, self: super: is the only right version.

The super nixpkgs

But what is this super argument useful for then ? In case you want to make some modifications to an existing package. Like a patch for example. Let’s assume that you need a specific patch for your firefox. You could define an overlay like this.

# In real life scenarios,

# you would probably patch firefox-unwrapped instead

self: super:

{

firefox = super.firefox.overrideAttrs (oldAttrs: {

patches = (oldAttrs.patches or []) ++ [ ./fixit.patch ];

};

}Using self here would make no sense, because it will end up being the very firefox you are trying to define. Nix will detect this loop, and raise the painful error: infinite recursion encountered described above.

It makes little sense to use self.fooBar in the definition of foobar itself. After all, the names have been chosen for their similarity with inheritance models. self (sometimes called this) is the final object, while super is a reference to the previous class in the inheritance hierarchy.

How much sense would this code make ?

class Animal {

String who() {

return "animal";

}

}

/// Just as for overlays, you should have used @super@

class Dog extends Animal {

String who() {

this.who() + " : dog";

}

}Now, you have all the keys to understand the concise diagram for overlays found on the nixos wiki. If you squint hard enough, you can even see the class diagram in there :-).

Rules, rules, rules

Now, just like three years ago, some corner cases make it hard to know when to use super and when to use self. There are some good examples in the NixCon presentation, but they do not make everything clear.

For packages, the rule is simple. Use self, except when you want to override some pre-existing recipe. In that case use super. The rule conforms to the inheritance model for classes.

For functions, and other values, it seems that super is the way to go. And it bugs me terribly since I defined a helper overlay for helper functions. As overlays have a precise order, using super may not find the function if your overlay happens to be included before the lib overlay…

After some investigations, it turns out the reason behind using self only for packages is grafting. And that concept, as well as its impact on the design of overlays, will be explored in the next post.